It is an article of faith (or at least urban legend) that Folk Music passed the baton to Rock on that tempestuous day in July, 1965 when Bob Dylan plugged in his electric guitar and shocked (thrilled?) the audience of the Newport Folk Festival. It is said that folk paterfamilias Pete Seeger was so mortified by the desecration of the acoustic shrine that was Newport that he literally wanted to pull the plug on Dylans’s sacrilege.

It is an article of faith (or at least urban legend) that Folk Music passed the baton to Rock on that tempestuous day in July, 1965 when Bob Dylan plugged in his electric guitar and shocked (thrilled?) the audience of the Newport Folk Festival. It is said that folk paterfamilias Pete Seeger was so mortified by the desecration of the acoustic shrine that was Newport that he literally wanted to pull the plug on Dylans’s sacrilege.

Cooler heads prevailed, and the once successor to Woody Guthrie’s legacy went on to sing three “electric” numbers beginning with “Maggie’s Farm.” The rest, as they say, was history. Host Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul & Mary fame, about whom more will follow), invited Dylan back for a couple of acoustic numbers, including “It’s all over now, Baby Blue,” which has since been viewed as his farewell to the world of folk music.2 The truth, while not quite as dramatic, was equally interesting. Not only had Roger McGuinn’s group “The Byrds” already recorded no fewer than four Dylan songs with electric accompaniment 3, but Dylan himself had charted (at 39) with “Subterraneum Homesick Blues,” in April of ’65 and had recorded the half-electric breakthrough album, “Bringing it all Back Home” earlier that year. Dylan had apparently been bitten by the electric bug even earlier. When he first heard the Beatles’s “I want to Hold your Hand,” he is reported to have said, “Did you hear that? Fuck! Man, that was fuckin’ great. Oh man, fuck.”4 I guess Bob must have liked them, as did we all.

When I first heard the Byrds’s “Mr. Tambourine Man,” on one of the album-oriented FM stations early in ‘65, I couldn’t imagine it being anything other than a Dylan song. Though quite familiar with his output up to that time, the song carried Dylan’s already massive songwriting talents to a new level. At the time, I wondered how he felt having his trademarked acoustic guitar sound tampered with in such a “commercial” way. He was already under fire within the orthodox folk community for having moved away from topical-political songs to more introspective numbers. 5

Bear in mind that, up until then, no self-respecting folkies would have countenanced the presence of amplified guitars in their midst. It wasn’t until I saw Dylan on the back of the Byrds’s album posing with McGuinn that I realized the electric sound had not only his acquiescence, but enthusiastic support.

“Mr. Tambourine Man” was an instant classic, punctuated by a McGuinn’s memorable opening riff in what may not have been the first electric twelve-string guitar ever to have been featured on record (give a listen to George Harrison’s Rickenbacker on “Hard Day’s Night”), but was certainly the most sonically dramatic. Take that, Pete Seeger! In any case, the genie was out of the bottle long before Newport. What was achieved at the Folk Festival in Newport that rainy July night was that a generation soon to follow Timothy Leary’s admonition to “tune in, turn, on and drop out,” had begun by plugging in. Lest Mr. Seeger feel slighted, the Byrds had given their unique treatment to one of Pete’s tunes (“The Bells of Rhymney”) on that same debut album, and entitled their second LP after his “Turn, Turn, Turn,” co-written, some say, by God. 6

To understand about how the golden age of rock came about and how singers like the Byrds, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the Mamas & the Papas, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon, The Loving Spoonful, Simon & Garfunkel, the Grateful Dead, and the Eagles (just to name a very few) came to life, it is important to go back to 1950. Up until that time, folk music was mostly for cafes, campfires, and union halls. A young group of unusually talented musicians (whose left-wing backgrounds subsequently led to their being blacklisted) teamed up with arranger Gordon Jenkins to have two smash singles. The group was called “The Weavers,” and they consisted of Ronnie Gilbert (their one female member), Fred Hellerman, Lee Hays, and the aforementioned Pete Seeger. Their songs were “Irene Goodnight,” and the Hebrew song “Tzena, Tzena, Tzena.”

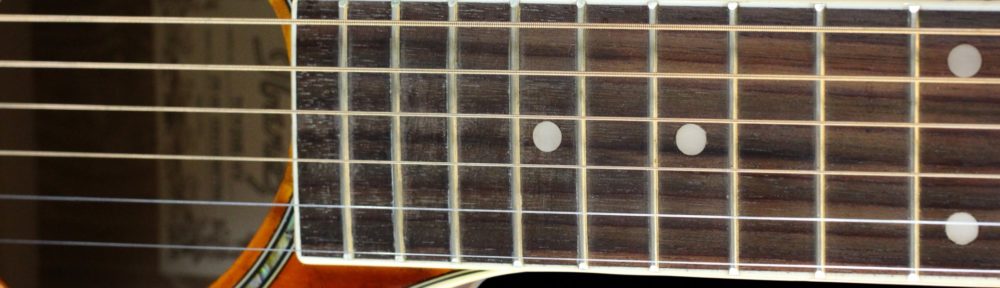

In addition to Hellerman’s guitar and Seeger’s banjo (which both played with uncommon virtuosity), Seeger occasionally played an unusual instrument—a guitar with 12 strings. For those unfamiliar with the 12-string, it has a deep and wonderfully “clangy” sound—like the traditional six-string guitar, but more so. Its only drawback is a tendency to drown out a voice and—oh yeah—the fact that it’s twice as hard to tune. Seeger learned about the instrument from the late black blues singer and “King of the Twelve-String Guitar,” Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter. Leadbelly literally sang his way to freedom, having twice received gubernatorial pardons from prison sentences following musical appeals.7 Though just six-months dead from Lou Gehrig’s disease, Leadbelly’s song “Irene Goodnight” sold two million copies, and soon it and the Weavers were known throughout America. Although they dropped a verse about taking cocaine, and changed “I’ll get you in my dreams,” to the tamer “I’ll See You in My Dreams,” the song succeeded beyond anything Leadbelly could have ever imagined. “Irene” became the year’s number one tune, with “Tzena” finishing at a not-too-distant thirteenth. 8

Leadbelly would have been almost as surprised to learn that his then obscure instrument would, within twenty years of his death, be played by more white, educated urbanites than had ever heard him perform. Seeger and protean folk-singers Oscar Brand and Bob Gibson would soon be joined on the 12-string by many folk groups that would feature its distinctive sound. Sales of the instrument, which had been virtually non-existent up to that time, skyrocketed. Among its many users were Judy Collins, John Denver, The Chad Mitchell Trio, the Rooftop Singers (a trio featuring not one, but two 12-string guitar players, one of whom, Erik Darling, had been Pete Seeger’s replacement with the Weavers), the New Christy Minstrels, the Brothers Four, the Journeymen, the Back Porch Majority, Paul Simon etc. etc. etc. 9 (Not inappropriately, the 12-String made an appearance among the members of the “neuftet” “New Main Street Singers”—a thinly-veiled take-off on the above-mentioned “New Christy Minstrels”—in the popular Christopher Guest “folkumentary” movie spoofing the folk-craze “A Mighty Wind.”)

In 1951, the Weavers charted with the familiar “On top of Old Smokey,” 10 but the “Red Scare” of the McCarthy years soon found them in an involuntary exile that lasted until their triumphant Carnegie Hall concert in 1955.11 With the Weavers in political eclipse, the brief presence of folk music on the charts ceased. Apart from Tennesse Ernie Ford’s version of Merle Travis’s “Sixteen Tons” in 1955 (not to be confused with “Sixteen Candles” by Johnny Maestro and the Crests), and Lonnie Donnegan’s “skiffle” version of Leadbelly’s “Rock Island Line in 1956, folk songs on the charts were few and far between. Even folksinger Harry Belafonte’s “Day-o” and the Tarrier’s version of it called “The Banana Boat Song” in 1957, was more a part of the Calypso tradition than folk music.

Interestingly, the success of Calypso music gave birth to a group who (although inspired by the Weavers) were single-handedly responsible for restoring folk music to the pop charts and bringing about the folk music revival (or what James Taylor refers to as “the great folk scare of the 60’s.”) 12 The group, two of whose members hailed from Hawaii and the third from California, chose the geographically improbable name “The Kingston Trio” precisely to invoke images of Jamaica and capitalize on Calypso music’s popularity.

The enormous popularity of the Kingston Trio spawned scores of folk duos, quartets, and other trios, each of whom were anxious to capitalize on the Trio’s success. Among these were groups such as the Limelighters, Peter Paul & Mary, the Highwaymen, the Journeymen, the Chad Mitchell Trio, Ian and Sylvia (see “Mitch & Mickey” from “A Mighty Wind”), the Brothers Four, Bud & Travis, The Smothers Brothers, the Halifax Three, and the Big Three. Of these, Peter, Paul & Mary were, by far, the most successful, arguably eclipsing even the Kingston Trio. The group’s most outspoken member, Peter Yarrow, once went as far as to suggest that his group (whose version of Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind” was the 17th most popular song of 1963) might even “influence a national election.”13 ( Yarrow’s speculation, however immodest, paled in comparison to the late John Lennon’s pronunciamento that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.”14) Secular or spiritual influences apart, I consider myself fortunate to have been a part of their musical time. I was, in fact, lucky enough to have spent time with, and introduced, both Peter, Paul & Mary and the Kingston Trio (but not, alas, the Beatles) at concerts, albeit thirty years apart!

Back in 1962, PP&M had come up to my college (Alfred University) as part of the Interfraternity Council Weekend. We had contracted to get the group for (if you’ll pardon the pun), a song. We had hired them on the basis of their first hit (“Lemon Tree”), at which time their asking price was something like $800. By the time they arrived on campus that December, their fees had risen to $1,200 (still an incredible bargain), but they, of course, honored the rate contracted to before the summer. In the months that followed, they became a huge success, well on their way toward commanding even higher fees than the Kingston Trio (whose going price was the then enormous sum of $5,000). As President of the IFC, one of my “perks” was to introduce the group. What I hadn’t bargained on was that our Treasurer (whose job it was to organize the weekend) was so busy supervising decorations for the dance, that he hadn’t arranged to meet them. As a result, I was rudely awakened from a rest I had only recently begun to learn that each of Peter, Paul & Mary (and their bassist) were waiting—alone—at the Alfred Lunch (a local eatery of limited fare and appeal). Hastily (and badly) dressed, I met them and spent the next several hours with the group as they made their diligent preparations for the concert. They carefully tested the auditorium where they were due to perform with their own mikes and sound-checks.

Fortunately, just before showtime, my roommate arrived with a tie, sport jacket, and dress shirt for me to “match” with my blue jeans and desert boots. Back then, “big weekend” college concerts such as this were dressy occasions. Peter and Paul, for example, performed in three-piece suits with tab-collar shirts. Imagine (just a very few years later) wearing a suit to, say, a “Grateful Dead” or “Jefferson Airplane” concert. They would have thought you were the FBI on pot patrol.

As a college-level (i.e. small-town clubs and campus events) folksinger, I relished the opportunity of getting substantial face-time with such a prominent group. One performance tip I utilize to this day from the kind and generous (Noel) Paul Stookey was his advice not to worry about appearing overly dramatic on stage. Understating your role, while admirable from a modesty standpoint, is lost on an audience, which has a right to expect some enthusiasm from performers. I guess that’s why they call it “performing.” As their recent PBS special, “Carry it On” demonstrates, PP&M’s commitment to both high quality music and issues of public concern has endured for over forty years.

Thirty years later (with two sons older than I was during the Peter, Paul & Mary concert), I was invited to introduce the Kingston Trio, which was playing at a summer concert series in Coney Island. In what clearly was a role-reversal from what would have been the case thirty years before, the Trio was opening for Judy Collins. Its most familiar member was Bob Shane, who had been with the group since its inception. Though grayer and heavier, his was still a familiar face. In meeting the rest of the Trio in their trailer, I did not recognize Nick Reynolds, on whom time had taken its toll. The once baby-faced little guy with the blonde crew-cut and the four-string guitar, looked like, well, a senior citizen. Once up on stage, however, the Trio (completed by George Grove, a very talented musician, who said his balding pate made him “follicly challenged”) performed with style and verve.

To anyone of a certain age, the mention of the names Peter, Paul & Mary and The Kingston Trio evoke many pleasant and justly deserved memories. Fortunately, both the Trio (in its various incarnations) and Peter, Paul & Mary (also showing their ages, but with original cast intact) have continued to perform and entertain. If either group is playing in your area, try to catch them. You won’t be disappointed. In this writer’s opinion, the Trio’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” and PPM’s “Blowing in the Wind” stand as the two best commercial folk songs ever recorded. Please give a listen and see if you agree. 15

But folk music—at least as a commercial medium—had seen its day. With Dylan and the Byrds leading the electrified charge, everybody was plugging in. A young man named Eric Burdon (of the Animals) hit the charts with an arrangement of an old folk-blues song, “The House of the Rising Sun.” In it he used a distinctive chord progression (Am, C, D, F, E7—as opposed to the standard Am, E7). This arrangement was identical to the one used by Dylan on his eponymous debut album. As a denizen of a long defunct Greenwich Village folk club called “The Gaslight,” I remembered hearing the late Dave Van Ronk play that song with his distinctive mournful rasp and rapid, feather-light brush strokes of the thumb. As an early mentor of Dylan, Van Ronk was surprised and disappointed that his protégé released the song before he had. 16 In the liner notes to his album, Dylan does credit the version to Van Ronk. Unfortunately, while I don’t imagine Dave saw a penny of the royalties from the Animals’s recording, “Rising Sun” made the charts on August 15, 1964, and for three weeks was the country’s number one hit! 17

A couple of weeks later, Barry McGuire, a former member of the New Christy Minstrels hit the charts with a shamelessly Dylanesque song called “Eve of Destruction.” Capitalizing on the “protest” motif then in vogue, “Eve” soon dislodged “House of the Rising Sun” from the coveted number one spot on the charts. 18

As Phillips’s title song “Creeque Alley” so well put it, “McGuinn and McGuire, still a-gettin’ higher…” The Byrds hit song “Eight Miles High” was symbolic of the height of their ascent. Indeed, Roger McGuinn had traveled a long distance from being a non-singing sideman for the Chad Mitchell Trio to be the lead singer of one of the country’s hottest groups. Similarly, Barry McGuire had stepped out from being one of a dozen or so anonymous “New Christy Minstrels” to having such a popular and controversial song that there was even an “answer” written to it, which, amazingly, made it into the Billboard “top 40.” For those with truly nothing better to do, check out “The Dawn of Correction.”19

While nothing succeeds like success, and Bob Dylan never had a number one hit, I think it fair to say that he had nothing to fear from McGuire as a lyricist, even when they both utilized the exclamatory “ah” to open a line. 20

In 1964, a former rock & roll duo known as Tom & Jerry, (AKA-Art & Paul) recorded an album of folk songs (traditional and composed) under their surnames, Simon and Garfunkel. One of these songs was a plaintive tone poem entitled, “The Sound of Silence.” Apart from its evocative lyrics, which spoke of a prophetic neon sign flashing its light against the silent darkness that keeps us from reaching out to others, its haunting melody made it a cult classic for the boys with the funny names. (I know, with “Sprung,” I’m one to talk.) And there it lay for a number of months, until some bright A&R man at Columbia Records, hip to the success of fellow Columbia artists Dylan and the Byrds, took S&G’s acoustic masterpiece, overdubbed drums, an electric guitar and electric bass and presto—twelve weeks on the chart, two of them at number one.21 Folk-rock had truly arrived.

Earlier in this piece, I had mentioned some of the more popular folk groups that had peppered the nation’s coffee houses and, in some cases, college campuses and larger urban venues. As the late 50’s rolled into the early 60’s, folk groups, with their feel-good harmonies and irreverent wit, began to supplant the jazz musicians that had, up until then, been the entertainment of choice at Homecoming and other “big” campus weekends. One group I remembered hearing and admiring when they came to my school in 1962 was “The Journeymen.” Led by a (yes) tall, dark and handsome young man named John Phillips, the other two members were Scott MacKenzie,22 a friend of his with the kind of angelic tenor voice that people have to be born with, and a superb instrumentalist named Dick Weissman. Clearly influenced by the Kingston Trio (as was virtually every group that followed on their coat-tails), the Journeymen had a slicker, tighter sound than the Trio, employing more sophisticated instrumental arrangements and vocal harmonies. Several years and three record albums later 23, the group split up. Phillips, having to honor some remaining commitments, reformed the group under the name, “The New Journeymen,” consisting of former Tarrier (“Banana Boat Song”) Marshall Brickman, who went on to be a co-writer with Woody Allen on several films,24 and a stunning young woman named Holly Michele Gilliam, whom he went on to marry and later transform into “Mama Michele.”25

To learn where things went from then, one need only listen to the words of their 1967 song, “Creeque Alley,” from which this piece gets its name. For those interested in the full details of this cleverly autobiographical tune (accompanied, appropriately enough, on John’s 12-string guitar), see the website “creequealley.com.” By the time the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were ruling the pop charts, there were a number of people performing either individually or with other folk groups who went on to form the nucleus of what went on to be known as folk-rock. Among them was a gawky young teen-ager named John Sebastian, who haunted various Greenwich Village coffeehouses. I heard him one open-mike night playing back-up harmonica (behind a folk-singer whose name is lost to memory and, now, antiquity) from one of the many mouth-harps that lined his vest. Good as Dylan was (and doubtless remains) on harmonica, you should really hear some early Sebastian. 26

Denny Doherty of “The Halifax Three,” joined forces with “Mama” Cass Elliot (nee Ellen Cohen), then with a group called “The Big Three.” After adding Sebastian (an alumnus of “The Even Dozen Jug Band”), and a heretofore unknown guitarist named Zal Yanovsky to become a quartet, Doherty suggested they change their name to “The Mugwumps.”27 These four split in half, Sebastian and Yanovsky to form “The Loving Spoonful” 28 and Denny and Cass, of course, to form the “Mamas and the Papas.” An interesting chart setting out the genealogy of the Mama’s and the Papa’s musical roots can also be found at creequealley.com.

For those of you unfamiliar with the music of these two groups (both of which are, deservedly in the rock n’ roll hall of fame), you should definitely acquaint yourself with them. They are, in my view, two of the three seminal folk-rock bands to have emerged from the folk community. While almost any of their individual albums are well worth listening to, you can’t go wrong with the available compilations.29 The third of these bands, you won’t be surprised to learn, is “the Byrds.” The hits these three groups produced are too numerous to mention, but the Spoonful’s “Do You Believe in Magic” captures the spirit of what they were all about. Just dig the words, “I can tell you about the magic that will free your soul, but it’s like trying to tell a stranger about rock and roll.”30 I felt that magic when I first heard Fats Domino, and I didn’t need pages of rock criticism to explain it. Like me, I’m sure you know it when you hear it. If you haven’t, put down this article immediately, and crank up your stereo!

Roger McGuinn (then known as Jim; the shift to “Roger” was for religious reasons since, I gather, abandoned), played guitar and banjo for one of the most clever and politically conscious of the folk groups, “The Chad Mitchell Trio.”31 Interestingly, when leader Chad Mitchell left the group to pursue an independent career, he was replaced by a young 12-string guitar player named John Denver, who went on to enjoy enormous popularity as a singer-songwriter, amassing 14 gold and 8 platinum albums, an achievement not even Dylan could match. 32

The Byrds enjoy an even more extensive genealogy than the Mamas & the Papas and the Loving Spoonful put together, but–in their case–it was more of a musical mitosis. From early 1965 up to 1973, the Byrds changed lineups as often as the New York Yankees, with McGuinn being the only constant. 33 What I found interesting about the Byrds’ development was how they changed sounds, from folk-rock to hard rock, to country, etc. As a look at his website (Roger McGuinn’s FolkDen) will show, McGuinn has not forgotten his folk roots, and remains committed to furthering the influence of traditional music.

Popular music, of course, continues to evolve, and the hit songs of, say, 2020, may be as different as today’s sounds are from the doo-wop beginnings of rock n’ roll. What is, however, easy to hear through the years, is the continuing influence of folk-rock. One would have to have listened long and hard to hear an acoustic guitar in rock music prior to, say, 1964. Try to imagine where modern music today would be without that warm sound of wood and steel strings.

While no one can gainsay the importance Bob Dylan has had on all things musical that followed him, the credit cannot go to him alone. Groups as disparate as “The Band,” “The Eagles,” “Crosby, Stills & Nash (and Young),” “Buffalo Springfield,” “The Who,” and “Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers,” as well as solo artists from Eric Clapton and Linda Ronstadt to Bruce Springsteen, all grew from the same soil that was tilled by pioneers such as the Mamas and the Papas, The Byrds and the Loving Spoonful. In the case of CSN&Y, David Crosby was one of the original Byrds.34

With apologies to all whose names I have omitted out of ignorance or oversight, the wonderful evolution of the best in popular music owes a debt to those who paved the way. I, as always, return to the Weaver’s who reminded us in the opening line of one of their most rousing numbers, “We are traveling in the footsteps of those who’ve gone before…”35

- See “No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan,” by Robert Shelton, New York, 1986. Dylan kept his “electric” plan secret. Shelton reported that Dylan, a week after the festival, was “stunned and distressed that he had sparked such controversy.” Shelton reported many boos and much displeasure. For a contrasting recollection, see “The Myth of Newport, 1965-It wasn’t Bob Dylan they were Booing” by Bruce Jackson, Buffalo Report, 8/ 26/02. As Shelton points out, Dylan was not the first person to go electric at Newport. Both the Butterfield Blues Band and the Chambers Brothers that year, and blues great Muddy Waters had done so the year before and no one booed, was shocked, or was anything but pleased.

- Ibid, “The Myth of Newport”

- On The Byrd’s debut album, en titled (appropriately enough) “The Byrds,” in addition to “Mr. Tambourine Man,” featured Dylan’s “Spanish Harlem Incident, “All I Really Want to Do,”(with an added “release”) and “Chimes of Freedom,” a version later covered live by Bruce Springsteen.

- No, I didn’t make that up. See “Positively Fourth Street,” by David Hadju, Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2001, page 197

- See Richie Unterberger interview with former ‘ Sing Out’ editor Irwin Silber, June, 2002 .(Look up “Irwin Silber and Dylan”on the web for the full interview) Silber, the editor of “Sing Out,” magazine (a left-leaning journal of folk music and thought that was the outgrowth of the “People’s Songs” movement of the late 40’s), had taken Dylan to task for abandoning his role as an agent of social change in the Woody Guthrie tradition.

- For those so moved, see Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 for Seeger’s lyrical inspiration.

- “The Life and Legend of Leadbelly,” by Charles K. Wolfe & Kip Lornell, Harper Collins, ’92. In 1925, while serving a 30 year sentence for a murder he claimed he was innocent of, Leadbelly performed a song written specially for the occasion of a prison visit by Texas Governor Pat Neff. It included the words “If I had you, Governor Neff, like you got me, I’d wake up in the mornin’ and set you free.” Neff liked it enough to grant a pardon. Back in jail some years later (this time in Louisiana, he was (with folklorist John Lomax’s help) pardoned by Governor O.K. Allen on his last day in office. (What is not true, but something that is widely believed was that Leadbelly was also pardoned by Governor Jimmie Davis of Louisiana, who had co-written “You are my Sunshine.” If true, it would have been the only gubernatorial pardon by one composer of another.) There was an interesting (if unrealistically heroic) movie of Leadbelly’s life called, simply, “Leadbelly.” It’s not bad, but for accuracy, you’re much better off reading the book.

- Kim Kwanghyon’s all-year end charts, 1950-2001

- For more on the history of the 12-String, see “The Origins of Twelve-String Power,” by Michael Simmons, Acoustic Magazine, 11/97 466242. While the two most famous folk groups, Peter, Paul & Mary and The Kingston Trio, primarily eschewed the 12-string in favor of the six (and in Nick Reynolds case, the tenor, or four-string) guitar, the Trio’s Dave Guard, played a Gibson twelve-string on the Trio’s “String Along” album. When Guard was replaced by John Stewart (a prolific songwriter, who later penned “Day Dream Believer” for the Monkees), he occasionally played the 12-string as well.

- Ibid, 1951. This traditional “camp” song had an unlikely rebirth in 1963, when old folkie Tom Glazer scored a surprise hit with his parody “On top of Spaghetti.”

- The album celebrating their return after several years on the blacklist, “The Weavers at Carnegie Hall,” Vanguard, 1956, VMD 73101, should be heard by anyone with an interest in folk music. It is a true “desert island” classic.

- See” James Taylor at the Beacon Theater,” (DVD) introduction to “Wanderin'” by Waldemere Hill.

- By recollection-“Saturday Evening Post,” sometime in 1964. Sorry for the imprecision.

- “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink… We’re more popular than Jesus; now.” As reported by Maureen Cleave in The Evening Standard, 3/14/66.

- While interestingly, both groups recorded “Blowing in the Wind,” and “Flowers,” neither—in my view– compared to the other’s rendition. For the preferred versions, see “Peter , Paul and Mary—Ten Years Together,” Warner Brothers LP 2952 and “The Very Best of the Kingston Trio” Capitol CDP 7

- You can hear Van Ronk’s rendition on “Just Dave Van Ronk,” MercuryRecords.

- “Top 1000 Rock Songs-Billboard’s top 40 1964-1999.

- Ibid.

- As www.ntl.matrix.com .tells us, “The Dawn of Correction” was performed by a group known as “The Spokesman,”(one of whom, David White, had been with 50’s rock n’ roll group “Danny and the Juniors,” who hit it big with “At the Hop?” If you remember them, you, like me, are approaching social security eligibility!) Among its lyrics were (with respect to the mutual assured destruction capabilities of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R), “The buttons are there to ensure negotiation, so don’t be afraid, boy, it’s our only salvation.” Not that “Eve” had inspired too much in the way of lyrical response. See the next footnote.

- Consider the following couplet from “Eve of Destruction: “Ah, you may leave here for four days in space, but when you return it’s the same ‘ol place” from “Eve. ” When you compare this with the chorus from Dylan’s “Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll: “Ah, but you who philosophize disgrace and criticize all fears, take the rag away from your face, now ain’t the time for your tears,” it’s easy to see that Dylan has the poetic edge over McGuire. In fairness, though, “Eve” made some good, strong points, and obviously struck a responsive chord with record buyers.

- Ibid 14. You can still hear the acoustic original (which I much prefer) on their “Old Friends” box set or on the original “Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.,” both on Columbia CDs.

- Scott went on to be the poster boy for flower power with his enormous1967 hit, “If You’re going to San Francisco (be sure to wear flowers in your hair”), penned by his friend (and fellow Journeyman) John Phillips. Some years ago, I saw a reconfigured Mama’s & Papas perform at New York’s “Michael’s Pub,” consisting of Scott MacKenzie in the Denny Doherty slot, MacKenzie Phillips (daughter of Papa John) as Michele, and Spanky McFarland (of Spanky and Our Gang) in the Mama Cass role, and the moribund John Phillips as himself. Just two seasons ago, Denny later brought his musical revue of life with the Mamas & Papas to Broadway, where it played a couple of months to mild reviews and attendance.

- “The Journeymen,” CCN 415-2,”Coming Attraction Live-The Journeymen CCN 416-2 ,” “NewDirections in Folk Music,” CCN 417-2..

- “Sleeper,” “Annie Hall,” “Manhattan.”

- “Papa John-The autobiography of John Phillips, Doubleday, 1986

- Listen to Sebastian backing Judy Collins on Eric Anderson’s evocative “Thirsty Boots,” (Judy Collins:3—(Electra) EKS 73900, or on “Night Owl”( named after the coffeehouse where, according to Creeque Alley, “Sebastian sat, and after every number they passed the hat.”), which can be heard on the Spoonful’s “Best of.” (see footnote #28)

- From Denny Doherty’s website “Dream a Little Dream.” According to Denny, the Mugwump name was taken from an animal found in Newfoundland which, like their music, defied easy categorization straddles a fence, “mug on one side, wump on the other.”

- See creequealley.com. The group took its name from the song “Coffee Blues” by blues legend “Mississippi” John Hurt. As for the double entendre, I don’t think the drug imagery hurt their popularity one bit.

- “The Best of the Loving Spoonful,”Kama Sutra (KLPS 8056),and “The Mamas and the Papas—All the Leaves are Brown,” MCA Records #112653

- Among their songs were “The John Birch Society,” “Barry’s Boys” (about 1964 G.O.P Presidential nominee Barry Goldwater who lost to “peace” candidate Lyndon Johnson), Tom Paxton’s”What did you learn in school today” and others.

- See John Denver website for this and additional information.

- See “Byrds Tree:An Historical Timeline,” from booklet accompanying their four-CD 1991 Box Set, “The Byrds,” Columbia From

- With Crosby revealed as the surrogate papa with Melissa Etheridge and Julie Cypher, perhaps the seeds of folk-rock have been passed on to another generation of musicians.

- From “When the Saints Go Marching in,” “When the Saints go Marching In,” by that great songwriting team, Trad & Anon. See footnote #10.